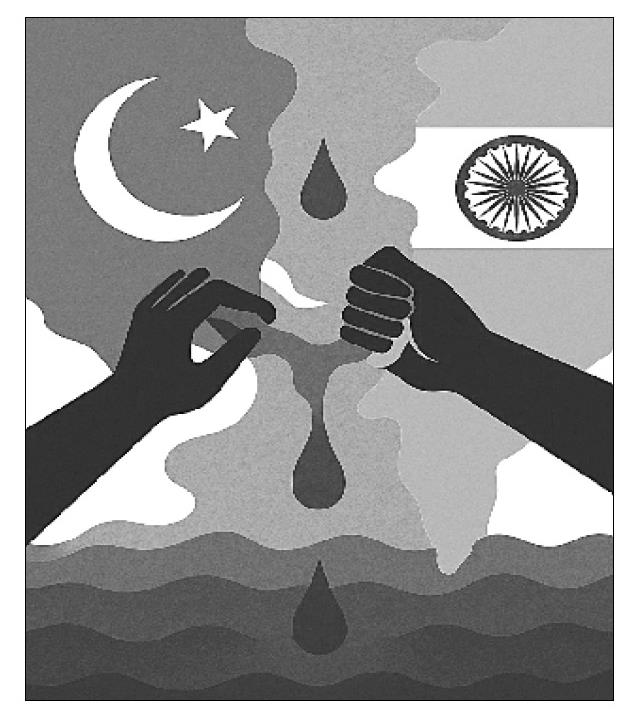

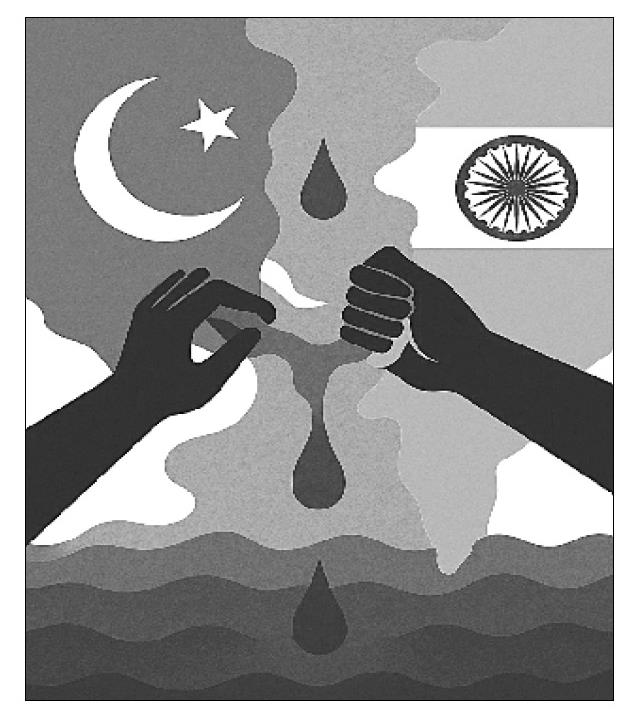

IWT is a perfectly valid instrument

2025-08-18

THIS is with reference to the article `IWT: its failure and future` (Aug 13), which raised some interesting points that merit consideration, but it largely missed the wood for the trees when it comes to the basic intent of the treaty. To say that the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) was a political agreement to earn the World Bank a few geopolitical dividends is too simplistic. Comments based on hindsight are easy, but the context in which the treaty was signed cannot be should not be ignored.

In line with the Indian leadership`s desire of making Pakistan an unviable state, India had stopped the flow of water in Central Bari Doab and Dipalpur canals that irrigated Pakistan`s Punjab province.

This was done on April 1, 1948, after the expiry of the standstill water agreement.

The Inter-Dominion Accord was signed in Delhi between the two countries a month later after five tense weeks of canal closure, which had caused a loss of Rs20 million to Pakistan.

The water acrimony reached a crescendo in 1951 when Pakistan and India were on the brink of war because of the water issue.

While Pakistan was invoking its historic usage rights, India refused to share water.

The threat of war led to mediatory efforts by David E. Lilienthal, an American technocrat, who proposed a solution to the World Bank that subsequently brokered the IWT, which provided a legal basis to Pakistan`s historical use and moralitybased claims. Besides, it also provided the much-needed funds for building dams and link canals.

It is worth noting that the seven per cent share of the western rivers conceded by Pakistan, as mentioned in the article, for non-consumptive and domestic use has not yet been utilised by India.

Since the geography in the case of Indus and Jehlum rivers prohibits large storagereservoirs to India, Chenab is the only river that is threatened by the illegal holding in abeyance of the treaty. What is worrisome is the possibility of water diversion from Chenab through gravity canals.

The crux of the water problem is the construction of projects by India that can give it the ability to alter the water flow of western rivers, allocated to Pakistan.

The Indians object on the premise of technological advancements in silt control in reservoirs that should be permitted to them to prolong the usable life of their hydroelectric projects.

The Pakistanis, fearful of Indian intentions, refuse to grant that capability which lies outside the scope of IWT. The whole issue, therefore, is not about the viability of the treaty, which is a perfect legal instrument.

Further,sayingthatthe treatyhas resulted in an ecocide is a gross exaggeration, as is the issue of sea water intrusion.

TheIndianstance ontheissueisrootedin hubris and bad faith, driven by Hindutva politics of exclusivism.

India has been moving goalposts, adding one spurious reason after another,like demographic changes, renewable energy commitments, climate change, and, finally, terrorism. None of the above reasons can be called unforeseenfactors that could not have been imagined at the time of IWT signing. And, hence, they remain legally invalid.

Pakistan should be ready to listen to Indian concerns, provided those are discussed under IWT, and not beyond it. Pakistan should employ all legal and diplomatic options to bring India back into the IWT fold.

While the kinetic option remains on the table, Pakistan has the good sense to know that it is an option of last resort.

Brig (retd) Dr Raashid Wali Janjua Islamabad